90 Years Ago: Woodhaven’s Unsolved Murder

By Ed Wendell

projectwoodhaven@gmail.com

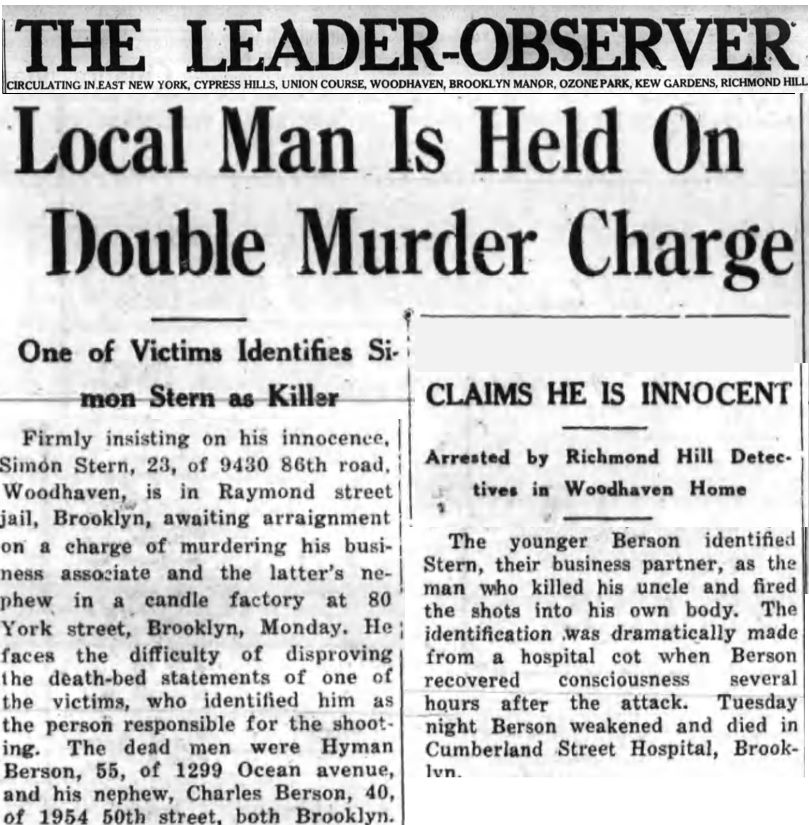

“Local Man Is Held On Double Murder Charge” read the headline in the Leader Observer 90 years ago. Here’s the story behind that headline.

It began in March of 1933 when police were called to the offices of the Waxcraft Candle & Crayon Company on York Street in Brooklyn. There they found one of the owners, Hyman Berson, shot to death. Nearby they found his nephew Charles, also shot and clinging to life.

Charles was able to identify their assailant, Hyman’s partner in the business, Simon Stern. Stern lived at 94th Street and 86th Road in the Brooklyn Manor section of Woodhaven, Queens.

Police traveled to the Stern household, a lovely attached home on a beautiful tree-lined street where they found the businessman eating dinner with his wife and son. They brought Stern to the bedside of Charles Berson where he pointed to Stern and, again, identified him as the killer just before dying from his wounds.

Stern was arrested and incarcerated without bail at the Raymond Street Jail, the notorious Brooklyn prison which operated from 1836 through 1963.

The trial began in November of 1933 and the prosecutors wasted no time laying out the case against the businessman.

First, they noted that Stern had ample motive to murder his partner, Hyman. Their business had been foundering and they were in debt. But the two businessmen had both taken out insurance policies worth $20,000 with each partner serving as the other’s beneficiary.

Next they told the jury that Stern owned a revolver, the same kind that would have produced the wounds that killed the two men. However, Stern was unable to produce the gun, claiming it had been lost in early 1932 when he lost a bag on the Sutter Avenue Bus in Brooklyn.

The driver of the bus testified that Stern did indeed report a lost bag on his bus but that Stern did not mention a gun when reporting the contents of the lost bag. Furthermore, Stern renewed the permit for his revolver with the local precinct in late 1932, months after he claimed to have lost it.

Woodhaven’s Simon Stern may have escaped justice in the 1933 slaying of Hyman and Charles Berson, but fate caught up with him on a lonely road in 1938 outside of Goshen, NY.

And finally there was the deathbed statement from Charles Berson, who stated in front of witnesses that Stern was the gunman.

Stern’s defense was led by Leo Healy, a former Brooklyn District Attorney and Homicide Court Judge appointed to that position by Mayor Jimmy Walker. Healy had resigned for health reasons shortly after being cleared of charges of corruption and spent the rest of his career as a famed defense attorney.

Healy told the jury about candle and crayon trust racketeers who had paid Charles Berson $150,000 to stay out of the candle business only to be double-crossed when he resumed business under a dummy name with Stern and his uncle.

Healy dismissed the missing gun, maintaining that it had been lost on that Brooklyn bus, explaining Stern’s permit renewal as an effort to retain pull with the local police when pulled over for traffic violations.

And finally, Healy noted that Berson’s dying declaration that Stern was the shooter was of no value because Berson had not been made aware that he was going to die. The law at the time stated that any person giving a dying declaration be fully aware that they were dying with no hope for recovery.

The jury spent three hours deliberating Stern’s fate before leaving prosecutors stunned by coming back with a verdict of Not Guilty.

Stern waited until the crowds left the courthouse before leaving. Outside, he was attacked by Charles Berson’s widow Sadie who, according to news accounts “punched, bit, kicked and battered him into a bloody pulp” before police could intervene.

Stern declined to press charges against the widow, saying “Probably if I were in her place I would do the same thing.” Stern returned to his Woodhaven home a free man.

The arrest of businessman Simon Stern of 94th Street and 86th Road in Woodhaven made headlines in the Leader Observer 90 years ago in 1933. The trial would keep Woodhaven riveted until a verdict was reached later that year.

Over the next few years, prosecutors kept investigating the murder while Stern opened a shoe store in Brooklyn. Stern was under secret indictment for the murders and the state was preparing to retry him in 1938 when he was killed in a head-on automobile collision outside of Goshen, in Orange County, New York.

And with that, the case was closed; the secret indictment was quashed and no one else was ever charged in the murders of Hyman and Charles Berson.